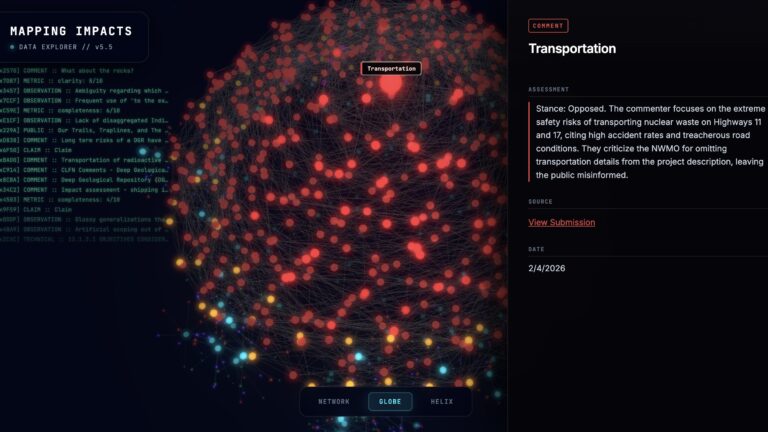

The visible expanse of cut timber in Northwestern Ontario illustrates the practice of clearcutting. While some trees remain standing on the horizon, this scene underscores the extensive removal of forest cover and its immediate impact on the ecosystem. Photo: Terri Bell

New Study Reveals Boreal Forest Degradation, Threatening Biodiversity and Caribou Habitat in Northeastern Ontario

Imagine a forest where ancient trees stand tall, where caribou roam freely, and where nature’s rhythm dictates the landscape. Now imagine that same forest, but with vast clear-cut areas, dwindling old-growth, and fragmented wildlife havens. A new study paints a sobering picture for Northeastern Ontario’s boreal forests, suggesting that current logging practices are pushing them towards degradation, not sustainable management. We see a lot of the same in Northwestern Ontario, so this report really caught our attention.

The research, titled “Emulation or Degradation? Evaluating Forest Management Outcomes in Boreal Northeastern Ontario,” published in Springer Nature, analyzed a decade of data across nearly 8 million hectares of public forests. What they found is alarming: our forest management isn’t mimicking nature’s cycles; it’s disrupting them.

Alarming Declines: Old Forests Vanishing, Wildlife Habitats Collapsing

The study’s most striking finding is that all five key indicators of forest health they examined showed results far outside what you’d expect in a healthy, natural forest. Instead, these trends point directly to timber maximization as the driving force. This means a continued decline in the rich diversity of life and essential services our forests provide, unless we make big changes.

One of the biggest concerns is the sheer amount of logging. Clearcutting rates are often higher than natural fire disturbances, which historically helped shape these forests. For example, some conifer forests are being harvested at rates far exceeding what’s sustainable for a 100-year cycle.

This rapid disturbance has led to a dramatic and troubling decline in our older forests:

- Vanishing Giants: Forests over 100 years old now make up only about 22% of the study area. In a natural landscape, you’d expect to see around 53% of these mature forests. If you look back historically, in areas like the Abitibi River, they were as high as 79%.

- Patchwork Forests: What old forests remain are often scattered and broken up. Imagine a large puzzle where most of the pieces are missing, and the remaining ones are tiny and isolated. That’s what’s the report says is happening to these vital old-growth areas.

The consequences are dire for the animals that call these forests home, especially those relying on mature and old-growth habitats:

- Caribou in Crisis: The report mentioned how majestic Boreal Caribou, already a threatened species, are particularly hard hit. Their “used” habitat has plummeted from a healthy 73% historically to a mere 12% when recent logging is considered. For their “preferred” habitat, the situation is even more dire: it’s dropped to a shocking 5% from a historical 53%. These levels of disturbance are considered “highly unlikely to sustain caribou populations.”

- Marten’s Struggle: The American Marten, a valuable furbearer, is also losing ground according to the report. Suitable habitat has shrunk to just 36% of the study area, compared to 76% historically. At a smaller scale, crucial for their daily lives, only 6% of the study area has suitable marten habitat, while historically it was 64%.

“Virtual Reality” Management: When Models Miss the Mark

Ontario’s forest management is legally bound to mimic natural disturbances. However, this study reveals a troubling disconnect: the government’s own planning targets for natural variability are significantly lower than what actually occurs in nature.

- For instance, the desired amount of old-growth forest in government guides is a mere 12.7%, a stark contrast to the 50.9% expected in a naturally managed forest.

- The study points to the province’s reliance on a computer simulation model called BFOLDS (Boreal Forest Landscape Dynamics Simulator). It appears this model, and how it’s used, can paint an overly optimistic picture, often underestimating the amount of old-growth and suitable wildlife habitat that should be present. It’s like planning for a forest in “virtual reality” that doesn’t quite match the real thing.

The researchers are clear: there’s no evidence that current forest management in Northeastern Ontario is maintaining the health of our ecosystems or effectively mimicking natural disturbances. Instead, the signs point to an ongoing degradation of our forests.

This study is a wake-up call, highlighting an urgent need to rethink how we manage our precious boreal forests to prevent further loss of biodiversity and vital ecosystem services.

What are your thoughts on these findings? Do you believe current forest management practices are truly sustainable?