In the crisp air of Northwestern Ontario, a blueberry bush unfurls its delicate beauty. These blossoms signal the start of a new season, a time when the landscape will be painted with the vibrant blue of ripening blueberries, a testament to the enduring beauty and natural abundance of this northern wilderness.

Why Northern Blueberries Beat the Store-Bought Kind—Every Time

Blueberry Season Begins in the North

In the woodlands of Northwestern Ontario, low bush blueberry plants are beginning to flower—marking the start of a season both eagerly anticipated and deeply rooted in local practice. For the second year in a row, our community-led food production program is preparing to harvest these wild berries by hand. We’re fortunate to have our own blueberry patches, and fields more around the community.

It’s May, and the timing of the bloom is critical. It reflects not only seasonal cycles but also the health of the surrounding ecosystem. Local monitoring of flowering stages and berry development helps ensure sustainable harvesting and long-term regeneration of berry patches. This process, grounded in observation and lived experience, allows communities to plan ahead, coordinate harvesting teams, and maximize both yield and stewardship.

Small Berries, Superior Quality

Wild blueberries differ significantly from their high-bush counterparts commonly found in grocery stores. They grow low to the ground, in shallow soils, without human intervention. These smaller berries are denser, more flavourful, and richer in antioxidants, making them a preferred choice for nutrition and taste.

The compact size of wild blueberries comes from their adaptation to challenging growing conditions—thin soils, unpredictable rainfall, and minimal nutrients. Yet these factors are what contribute to their deep blue pigment, rich taste, and higher concentration of beneficial compounds. Wild berries often contain nearly double the antioxidant capacity of cultivated ones, and their natural resilience translates into hardier fruit that holds up well during freezing and processing.

The Problem with Store-Bought Blueberries

Commercially farmed blueberries are often bred for size, uniform appearance, and shipping durability. These high-bush varieties are grown using irrigation systems, fertilizers, and pesticides, resulting in fruit that is large but often watery and bland. In contrast, wild blueberries grow naturally, requiring no synthetic inputs, and support a healthier local ecosystem.

Factory farming of blueberries, especially in southern regions, contributes to soil degradation, overuse of water resources, and habitat loss. These monocultures are designed for global markets, not local nourishment. Wild harvesting, on the other hand, maintains biodiversity and strengthens reciprocal relationships between people and the land. It offers not just a better berry, but a better way of producing food—one that values sustainability over scale.

Wild, low bush blueberries are slow to spread and mature. Unlike cultivated crops that are planted annually, wild blueberry plants expand through underground rhizomes—a process that can take years. It may take five to ten years for a wild patch to establish fully, and even longer for it to produce berries in abundance. Growth is influenced by fire cycles, soil conditions, and surrounding plant competition. Because of this long timeline, good patches are rare and often passed down as local knowledge across generations. Overharvesting or trampling can set a patch back for years, making careful stewardship essential.

Harvesting Food, Building Resilience

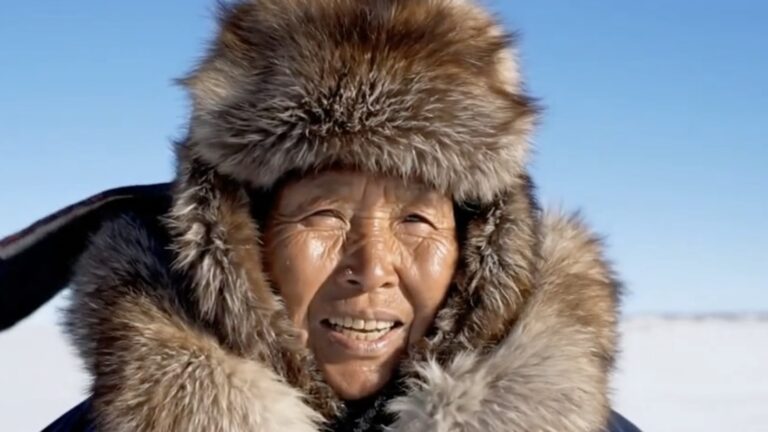

Beyond taste and nutrition, the wild blueberry harvest contributes directly to local food security and sovereignty. The berries are gathered, processed, and shared within the community, reducing dependence on external food systems. Fresh or preserved, they support year-round use in meals, baking, and traditional foods. The harvest process also strengthens ties between generations, as youth and elders work together on the land.

Our food production and food sector entrepreneurship program, launched in 2023-2024 increases access to healthy food, and works to build long-term capacity. Skills like identifying prime picking areas, learning preservation methods, and coordinating harvest crews are being passed on and expanded each season. What begins as a berry harvest becomes an entry point for deeper conversations about climate change, land use, and cultural continuity. It is a model of what local, land-based food systems can look like: community-directed, ecologically sound, and grounded in place.