The sun begins its descent, casting a golden hue over the serene waters and the rugged terrain. The sky is painted in shades of orange and pink, highlighting the tranquil yet vibrant atmosphere of the coming night across the western shores. Photo: Tony Eetak

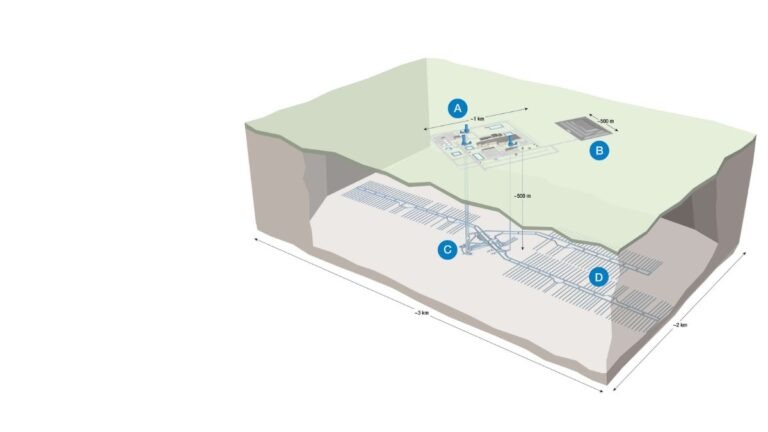

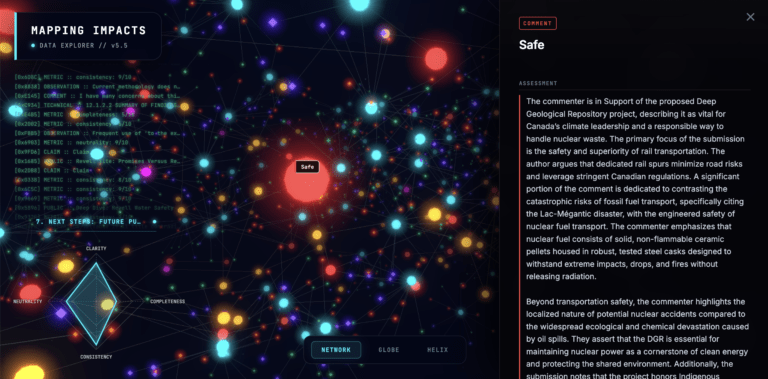

What are public comments saying about the NWMO Deep Geological Repository for Nuclear Waste Fuel and it’s potential impacts on the environment and society?

Our initial review of public submissions to the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada regarding the Revell Site Deep Geological Repository (DGR) reveals a highly polarized situation with a dominant majority expressing strong opposition. While a minority of stakeholders support the project based on economic revitalization and confidence in nuclear engineering, the overwhelming sentiment is characterized by deep distrust of the proponent (NWMO), fear of environmental catastrophe, and rejection of the regulatory process itself.

A significant portion of “Neutral” submissions are not indifferent; rather, they represent conditional stances that refuse to endorse the project without the inclusion of transportation risks in the federal scope or the establishment of rigorous liability frameworks. The data indicates a profound lack of social license, particularly regarding the transportation of waste through non-host communities.

- Support: 10%

- Opposed: 76%

- Neutral/Undeclared: 14%

Click here to read the full set of comments on the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada web site.

Language Analysis

Supporters use: Words focused on technical confidence, economic gain, and duty. Common terms include “science-based,” “opportunity,” “responsibility,” “mandate,” “robust,” “proven technology,” “revitalization,” “prosperity,” “misinformation” (referring to critics), and “common sense.”

Opponents use: Words focused on existential threat, moral failure, and uncertainty. Common terms include “risk,” “unproven,” “experiment,” “abandonment,” “poison,” “catastrophic,” “hubris,” “madness,” “bribe” (referring to financial incentives), “coercion,” “recipe for disaster,” “forever,” “legacy,” and “dump.”

Procedural Fairness & The 30-Day Window

A critical procedural failure identified across numerous submissions is the inadequacy of the 30-day public comment window. Stakeholders characterize this timeline as a “functional barrier to entry” and a “mockery” of democratic engagement. The primary grievance is the disproportionate ratio of information volume to review time; the Initial Project Description (IPD) and associated documents exceed 1,200 to 1,300 pages of complex technical, geological, and engineering data. Commenters argue that expecting volunteer-run community groups, Indigenous elders, and working citizens to digest, analyze, and respond to this volume of material within one month is “patently unfair” and effectively disenfranchises the public. This compressed schedule is repeatedly cited as evidence that the regulatory process is designed to favor the proponent by limiting the capacity for meaningful independent scrutiny.

Furthermore, our review reveals significant accessibility barriers that compounded the timeline issues. Submissions note that physical copies of the IPD were scarce or restricted to on-site viewing in limited locations, forcing a reliance on digital access in regions with poor internet connectivity. Stakeholders reported technical glitches with the digital portal and a lack of “good faith” notification, with some residents only learning of the comment window days before it closed. The overlap of the comment deadline with the deadline for participant funding applications was also flagged as a procedural error, forcing groups to apply for funding to review a document they had not yet had time to read. These procedural deficiencies have generated a widespread perception that the assessment is being “fast-tracked” at the expense of due diligence.

Transparency & Information Access

A significant volume of submissions identifies procedural barriers that stakeholders argue have compromised the transparency of the regulatory review. Multiple commenters, including those in [Ref: 245, 244, and 236], formally object to the 30-day public comment period, characterizing it as functionally inadequate for a project of this magnitude. Stakeholders note that the requirement to review over 1,200 pages of technical documentation within a single month creates a “functional barrier to entry” that disenfranchises volunteer groups and the general public [Ref: 223, 116]. Commenter [Ref: 140] describes this timeline as a “mockery” of the assessment process, arguing that it is impossible to identify gaps in environmental and health risk assessments without sufficient time to master the extensive material provided.

Beyond the timeline, specific concerns regarding information accessibility and digital barriers were raised. [Ref: 207] and [Ref: 200] report that physical copies of the Initial Project Description were scarce or restricted to on-site viewing, and that reliance on digital portals excluded residents with limited internet access or technical literacy. Furthermore, [Ref: 85] documents technical failures within the submission portal that prevented public participation. Allegations of information suppression were also recorded; [Ref: 238] claims that the proponent removed specific research papers from their website after safety questions were raised, while [Ref: 254] and [Ref: 242] argue that the exclusion of transportation logistics from the project scope amounts to “project-splitting,” effectively hiding the risks associated with the movement of waste from the primary transparency mechanism.

The disparity between the volume of data presented and the time allotted for review has led to accusations that the process is designed to obfuscate rather than inform. [Ref: 67] argues that the brief window prevents communities from moving beyond “promotional narratives” to conduct independent verification. Similarly, [Ref: 21] asserts that the lack of broad public awareness regarding the project’s risks indicates a failure in the proponent’s accountability and outreach efforts. These procedural deficiencies are cited by [Ref: 164] as evidence of a “blatant disregard” for public engagement, undermining the legitimacy of the transparency mandate governed by the Impact Assessment Agency.

Allegations of Secret Agreements & Conduct

Serious allegations regarding the conduct of the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) and the integrity of host community agreements appear frequently in the dataset. [Ref: 223] and [Ref: 200] raise concerns regarding “virtual gag orders” and the confidentiality of the hosting agreement with the Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation (WLON). Commenters argue that these non-disclosure clauses prevent public and regulatory oversight of environmental and social safeguards, creating a “transparency barrier” [Ref: 69]. Furthermore, [Ref: 116] alleges that the process has been characterized by “secret agreements” that have led to internal social fragmentation and a breakdown of trust within the region.

Financial incentives offered to potential host communities have been explicitly characterized by multiple stakeholders as “bribes” or “economic coercion” rather than genuine aid. [Ref: 254] and [Ref: 231] suggest that payments, such as the provision of a fire truck or large cash sums, exploit the economic vulnerability of “dying” towns to secure consent. [Ref: 238] alleges that these financial distributions amounted to bribery, while [Ref: 139] describes the focus on financially desperate communities as “deceitful and sneaky.” Additionally, [Ref: 192] and [Ref: 183] highlight a perceived inequity in these financial arrangements, noting a significant disparity between the funds negotiated for Ignace versus those for WLON or South Bruce, which has fostered resentment and allegations of bad faith negotiation.

Concerns regarding the misuse of funds and the strategic manipulation of the regulatory scope were also identified. [Ref: 189] accuses the proponent of “project splitting” to avoid federal scrutiny of transportation risks, a tactic described by [Ref: 200] as a collusion to “divide and conquer” the public. [Ref: 63] raises a red flag regarding the absence of a detailed budget, arguing that because the industry receives government subsidies, the project is indirectly taxpayer-funded and requires greater financial transparency. These submissions collectively suggest a perception among stakeholders that the governance of the project prioritizes the suppression of dissent and the purchase of consent over ethical conduct.

Democratic Integrity & Public Trust

A profound erosion of public trust in the regulatory bodies and the proponent is a recurring theme. [Ref: 251] and [Ref: 141] characterize the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) as a “captive regulator” funded by the industry it oversees, leading to a perceived lack of objective oversight. This sentiment is echoed in [Ref: 5], which cites survey results indicating that 96% of respondents are uncomfortable with the nuclear industry managing the NWMO. [Ref: 247] describes the proponent as “entitled,” arguing that the Initial Project Description functions more as a political mission statement than a factual document, which diminishes democratic accountability.

The integrity of the “willing host” model is heavily contested, with stakeholders arguing that the process manufactures consent while ignoring broad opposition. [Ref: 200] and [Ref: 116] allege that the regulatory process is designed to “manufacture consent” by pitting communities against one another. [Ref: 249] and [Ref: 161] argue that the definition of consent is democratically flawed because it excludes “corridor communities” and downstream residents who bear the risks of transportation but are denied a voice. [Ref: 7] and [Ref: 34] emphasize that despite the agreements with Ignace, widespread opposition remains among Treaty #3 First Nations and other regional bodies, suggesting that the project lacks a genuine social license.

Finally, the perception of the project as anti-democratic is reinforced by allegations that the proponent and regulators are ignoring petitions and dissenting voices. [Ref: 254] and [Ref: 192] argue that the process has been manipulative, targeting vulnerable populations while ignoring the concerns of the broader region. [Ref: 126] characterizes the current regulatory process as a “mockery of democratic rights,” while [Ref: 144] questions the democratic legitimacy of a private organization making decisions with multi-millennial consequences. The cumulative effect of these concerns is a widespread belief among opponents that the outcome is predetermined and that the governance structure fails to protect the public interest [Ref: 223].

Environment

Stakeholders have raised significant alarm regarding the hydrological implications of siting the repository at the headwaters of the Wabigoon and Turtle-Rainy River watersheds. There are alleged risks that radionuclides could leach into groundwater and surface water, eventually contaminating downstream systems including Lake of the Woods and Lake Winnipeg. Commenters argue that the interconnectivity of these water bodies means a containment failure could have transboundary consequences, potentially affecting Manitoba and the United States. The proximity of the site to the Great Lakes basin was also noted as a critical vulnerability, with critics asserting that any risk to these vital freshwater resources is unacceptable.

Technical concerns regarding the long-term stability of the Canadian Shield were prominent in the submissions. While the proponent characterizes the host rock as stable, opposing submissions cite the potential for microscopic fissures, seismic activity, and the geological stress of future glacial cycles to compromise the repository’s integrity over the required million-year containment period. Specific technical challenges were raised concerning the “thermal pulse” generated by high-level waste; critics allege that this heat could degrade the bentonite clay buffer and induce fracturing in the surrounding rock, thereby creating pathways for radioactive migration. Skepticism was also expressed regarding the reliance on computer modeling over physical evidence for such extended timelines.

The potential impact on local biodiversity and pristine wilderness areas remains a point of contention. Submissions highlighted the risk of bioaccumulation of radioactive isotopes in the food web, specifically threatening species such as moose, migratory birds, and fish populations essential to local tourism and Indigenous subsistence. Furthermore, critics characterized the Deep Geological Repository concept as a form of “abandonment,” arguing that burying waste precludes future monitoring or retrieval should the engineered barriers fail. There is a pervasive concern that human-made structures cannot guarantee environmental isolation for the duration of the waste’s toxicity, leading to allegations that the project creates an intergenerational environmental debt.

Transportation

The logistics of moving high-level nuclear waste from Southern Ontario to the proposed site generated substantial opposition, particularly regarding the suitability of Highway 17 and Highway 11. Commenters described these routes as hazardous, citing frequent closures due to severe winter weather, ice, and poor visibility. The infrastructure is frequently characterized as inadequate for the proposed volume of heavy transport—estimated at two to three shipments daily for decades—with specific references to narrow two-lane sections, lack of shoulders, and dangerous rock cuts. The risk of collisions with wildlife, notably moose, was repeatedly identified as a statistical inevitability over the project’s operational phase.

Safety concerns regarding the transport of radioactive materials were frequently described by objectors as a “Mobile Chernobyl” scenario. Stakeholders expressed deep apprehension that a derailment or trucking accident could result in a radiological spill, potentially contaminating the Lake Superior watershed or isolating communities by severing the Trans-Canada Highway, which serves as a vital national supply artery. A critical socio-economic red flag raised in multiple submissions is the alleged lack of emergency response capacity in rural and northern regions. Commenters noted that many corridor communities rely on volunteer fire departments that are reportedly ill-equipped and untrained to manage high-level radioactive containment failures.

A recurring regulatory objection involves the exclusion of transportation risks from the formal scope of the Impact Assessment. Many submissions accused the proponent of “project-splitting” by treating the repository and the transportation network as separate entities. Critics argue that the transport of waste is an integral component of the project and that excluding it prevents a comprehensive evaluation of cumulative risks to “corridor communities.” These stakeholders assert that the assessment is fundamentally flawed without a rigorous federal review of the potential for accidents, radiation exposure during transit, and security threats over the 50-year shipping timeline.

Indigenous Peoples

A significant portion of the submissions centers on the protection of Indigenous rights and the interpretation of “consent” within Treaty #3 territory. Numerous commenters allege that the current site selection process fails to meet the standards set by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), specifically the requirement for Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC). While the proponent has established a relationship with the Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation (WLON), strong opposition has been voiced by other regional Indigenous groups, including Eagle Lake First Nation and Grassy Narrows First Nation. These communities argue that the project threatens their inherent treaty rights and traditional land uses, with specific concerns raised regarding the potential for radioactive contamination of the Wabigoon and Turtle-Rainy River watersheds, which are vital for sustenance, culture, and spiritual practices.

The concept of a “willing host” has generated considerable controversy and perceived social fragmentation. Submissions suggest that the Nuclear Waste Management Organization’s (NWMO) engagement strategy has created a “divide and conquer” dynamic, pitting First Nations against one another. Commenters point to the exclusion of downstream communities and those along transportation corridors from the decision-making matrix, arguing that consent should be required from all Nations whose territories are crossed or potentially impacted, not just the immediate host community. There are allegations that the process ignores the collective decision-making protocols of the Anishinaabe people, with some commenters asserting that the project violates “Original Law” and the sacred stewardship responsibilities entrusted to Indigenous youth and elders.

Furthermore, ethical concerns regarding “economic coercion” are prevalent throughout the data. Many commenters characterize the financial incentives and partnership agreements offered to Indigenous communities as a form of bribery designed to exploit economic vulnerabilities. Critics argue that high poverty rates and a lack of basic infrastructure in northern communities make it difficult for leadership to refuse the financial influx associated with the project, thereby compromising the voluntary nature of any consent granted. This is compounded by references to historical trauma, particularly the legacy of mercury poisoning at Grassy Narrows, which fuels a deep-seated distrust of government and industrial assurances regarding environmental safety.

Socio-Economic Impacts

The socio-economic feedback reveals a sharp dichotomy between projected economic benefits and fears of a “boom and bust” cycle. While a minority of supporters anticipate job creation and regional revitalization, a significant number of commenters express skepticism regarding the long-term stability of these economic gains. Concerns have been raised that the employment opportunities may be temporary, specialized, or filled by transient workers rather than local residents, potentially leaving the community with expanded infrastructure liabilities once the construction phase concludes. Furthermore, residents in regional service hubs like Dryden allege that they may bear the burden of increased demand on social services, policing, and emergency response without receiving the direct financial compensation afforded to the host municipality of Ignace.

Infrastructure and public service capacity are cited as major areas of vulnerability. Submissions highlight existing shortages in housing, healthcare, and emergency services in Northwestern Ontario, arguing that the influx of a large workforce could exacerbate these deficits. Specific concerns were raised regarding the ability of local volunteer fire departments and rural hospitals to manage the risks associated with a major industrial nuclear facility or a transportation accident involving radioactive waste. Commenters fear that the project could strain municipal resources to the breaking point, leading to a degradation of quality of life for long-term residents, particularly seniors and those on fixed incomes who may face rising costs of living.

A pervasive concern regarding “stigmatization” threatens the region’s existing economic base, which relies heavily on tourism, hunting, and fishing. Business owners and residents argue that rebranding the “pristine wilderness” of Northwestern Ontario as a “nuclear waste dump” could deter tourists and depress property values. There is a fear that the reputational damage associated with hosting high-level radioactive waste will irreversibly harm the outdoor recreation industry, which is viewed as a sustainable, long-term economic driver. Additionally, the “corridor communities” located along the transportation routes argue they face a scenario of “all risk and no benefit,” bearing the potential socio-economic costs of accidents and road closures without sharing in the project’s financial incentives.

Final Conclusion

The aggregate data from the public comment period indicates a profound lack of social license for the Deep Geological Repository as currently proposed. The opposition is not merely technical but is deeply rooted in procedural, ethical, and socio-economic grievances. The overwhelming demand from stakeholders is for the inclusion of transportation risks within the formal scope of the assessment. The alleged “project splitting”—excluding the logistics of moving nuclear waste from the repository assessment—is viewed by the public as a critical regulatory failure that undermines the legitimacy of the entire process. Without a holistic review that incorporates the thousands of kilometers of transit corridors, the assessment is widely perceived as incomplete and legally vulnerable.

Given the complexity of the issues raised—ranging from the geological stability of the Canadian Shield over a million-year timeframe to the intricate legalities of Indigenous treaty rights and the potential for transboundary watershed contamination—a standard environmental review appears insufficient. The evidence necessitates a referral to an independent Review Panel with full public hearings. Only a rigorous, transparent, and arm’s-length process can adequately address the significant allegations of economic coercion, the scientific disputes regarding containment integrity, and the widespread demand for a “cradle-to-grave” assessment that includes the transportation of hazardous materials through populated centers.