Field Test at Revell Site

The duct tape was failing. That was the first problem. The second problem was that Ben couldn’t feel his thumbs well enough to peel off a fresh strip. The wind out here on the ridge wasn’t just moving air; it was a physical weight, pushing against the tripod legs and snapping the loose end of the ethernet cable against the grey granite like a whip. It smelled of wet iron and dying pine needles.

“It’s drifting again,” Jordan said. He didn’t look up from the tablet, his hood pulled so tight around his face that only his nose and the fog of his breath were visible. “The horizon line on the stitch. It’s wobbling.”

“It’s the wind shaking the rig, Jordan. It’s not software,” Ben snapped, instantly regretting the edge in his voice. He jammed his hands into his armpits, hunching his shoulders against the biting dampness of October in Northwestern Ontario. “Give me a second.”

Stacey was crouched a few metres away, collecting samples of the ambient sound with the boom mic. She looked like a statue wrapped in Gore-Tex, pointing the fuzzy deadcat windscreen at a patch of moss that wasn’t making any noise at all. She turned, her boots scraping loudly on the abrasive rock.

“We need the ambient silence,” she said, her voice muffled by a scarf. “That’s what the brief said. ‘The silence of stability.’ If you guys keep yelling about the horizon line, all we’re going to get is ‘The angsty tech support of stability.'”

Ben finally managed to snag the edge of the tape roll with his teeth, ripping a jagged strip. He wrapped it aggressively around the base of the panoramic camera, securing the battery pack that had been flapping loose. This wasn’t the sleek, lab-perfect setup they saw in the tech blogs. This was three GoPros rigged together with 3D-printed brackets and hope, perched on a rock that had been sitting here for a billion years waiting for someone to point a lens at it.

“Okay,” Ben breathed out, stepping back and checking the spirit level bubbles. “Okay. It’s solid. Jordan?”

“Checking… yeah. Better. We have sync,” Jordan muttered, tapping the screen with a stylus because his gloves were too thick for the touch sensors. “Rolling in three. Two. Don’t move.”

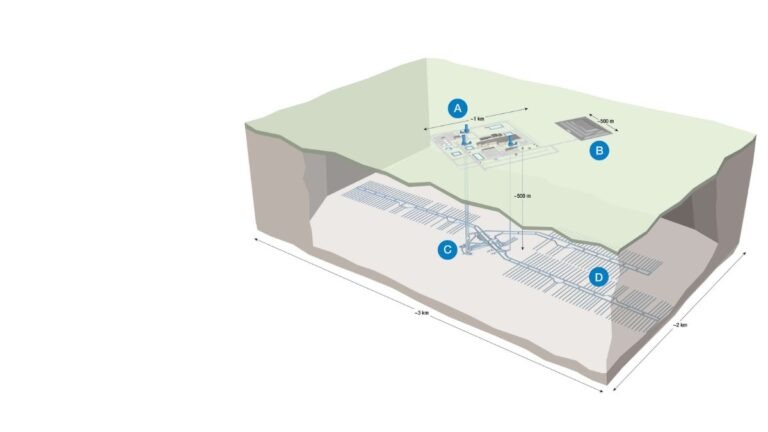

Ben froze. He looked out over the landscape. It was desolate and beautiful in a way that didn’t ask for permission. Endless rolling hills of shield rock, punctuated by black spruce and pockets of muskeg. This was the Revell site. Or near enough to it. The place where the government planned to bury the spent fuel. The ‘Deep Geological Repository’. It sounded like something from a movie, but right now, it just looked like a lot of wet rocks and grey sky.

He focused on the texture of the granite under his boots. Pink and grey feldspar, quartz, mica. Crystalline bedrock. Stable. That was the word everyone used. Stable. It wasn’t going anywhere. It hadn’t moved since the continents were a single lump, and it wouldn’t move for another ten thousand years. That was the pitch.

“Cut,” Jordan said. “That’s five minutes. My fingers are gonna fall off.”

“Pack it,” Ben said, already reaching for the release latch. “Let’s get back to the garage before the sleet starts.”

* * *

The transition from the biting wind of the ridge to the smell of sawdust and stale coffee in Ben’s uncle’s converted garage was abrupt. The heat from the propane heater hit them like a wall. It was a messy space—half woodshop, half edit suite. Monitors were propped up on stacks of plywood, and tangles of HDMI cables snaked around a bandsaw that was currently serving as a desk.

Jordan dumped the gear bag on the workbench with a heavy thud, immediately peeling off his gloves and holding his hands in front of the heater’s grate. “I hate field days. Why can’t we be ‘studio-based researchers’?”

“Because the studio doesn’t look like the end of the world,” Stacey said, unwinding her scarf. Her cheeks were bright red. She pulled a laptop out of her backpack and cleared a space on the workbench, pushing aside a half-eaten bag of dill pickle chips. “And because we need the textures. We need the real-world data.”

Ben sat down at the main computer, a tower he’d built from scavenged parts and eBay finds. He slotted the SD cards into the reader. “Data is ingesting. Let’s see if the wind ruined the stitch.”

While the progress bar crawled across the screen, Stacey opened a browser on her laptop. “So, while you guys were complaining about the weather, I was reading up on that lead I found last night. The place in China.”

“The other rock pile?” Jordan asked, grabbing a handful of chips.

“Beishan,” Stacey corrected him, scrolling through a PDF. “It’s in Gansu province. Near the Gobi Desert. Listen to this: ‘Stable crystalline bedrock, capable of safely isolating radioactive materials for thousands of years.’ Sound familiar?”

Ben spun his chair around, resting his chin on the backrest. “Granite is granite, Stacey. Physics works the same everywhere.”

“Yeah, but look at the approach,” she insisted, turning the screen toward them. It was a translated academic paper, dense with diagrams. “Multi-barrier approach. Hydrogeological tests. In-situ simulations. They’re doing the exact same thing we are. They’re drilling into the same kind of ancient rock to bury the same kind of problem.”

Ben leaned in, squinting at the photos in the article. The landscape looked different—arid, brown, dusty—but the rock… the rock looked exactly like the stuff he’d just been standing on. Fractured granite. It was uncanny. “Okay. So they have a Revell site too. What’s that got to do with our film?”

“Scroll down,” Stacey said, tapping the arrow key. “Look at who is doing the research. Lanzhou University. Specifically, the School of Nuclear Science and Technology.”

“Riveting,” Jordan deadpanned. “Maybe we can swap radiation readings.”

“No, look further,” Stacey said, her voice rising in pitch slightly, the way it did when she was onto something. She navigated to a different tab. “I went down a rabbit hole on their website. They have a massive media department. Researchers at Lanzhou University are looking at AI and immersive tech. VR. AR. The exact same stack we’re trying to use.”

Ben looked closer. The webpage showed a group of students wearing VR headsets, standing in front of a green screen. There were diagrams of ‘AI-Assisted Scriptwriting’ and ‘Virtual Production for Scene Simulation’.

“Wait,” Ben said, pointing at the screen. “Is that… are they generating terrain maps using photogrammetry?”

“‘Virtual production to simulate film sets and lighting conditions’,” Stacey read aloud. “‘Reducing the cost of trial-and-error on real sets.’ Ben, they’re doing exactly what we’re trying to do. But look at their gear.”

Ben looked. It was impressive. Clean, professional mocap suits. High-end cinema cameras. Not three GoPros taped together. “Okay, now I’m depressed. They’re actual scientists. We’re just three kids in a garage in Northern Ontario pretending to be a production company.”

“We aren’t pretending,” Jordan said, surprisingly defensive. “Our audio is clean. And that stitch is going to work.”

“That’s not the point,” Stacey said. “The point is, there are kids our age, right now, in Gansu, dealing with the exact same weird intersection of things. Nuclear waste. Ancient rock. Future tech. And…” she paused, clicking another link, “…ethical considerations of AI authorship.”

Ben rubbed his eyes. He was tired. The cold had sapped his energy, and the warm room was making him drowsy. But this was interesting. It was weirdly specific. “So, what? You want to copy their paper?”

“I want to talk to them,” Stacey said. She looked at Ben, then at Jordan. “Think about it. We’re telling a story about the Repository here. About how this land is going to hold this waste forever. They’re telling the same story there. What if we combined them? What if we used the VR space to link the two sites?”

Jordan stopped chewing his chip. “Like… a portal?”

“Like a data merge,” Ben said, his brain starting to wake up. He spun back to his monitor. The footage had finished importing. He clicked on a file, and the 360-degree view of the Revell ridge popped up. He dragged the mouse, spinning the view. Grey rock. Grey sky. “If they have photogrammetry data of the Beishan site… and we have this…”

“We could build a virtual environment where you walk on our granite and step onto theirs,” Stacey finished his thought. “A shared geology.”

“Do they speak English?” Jordan asked.

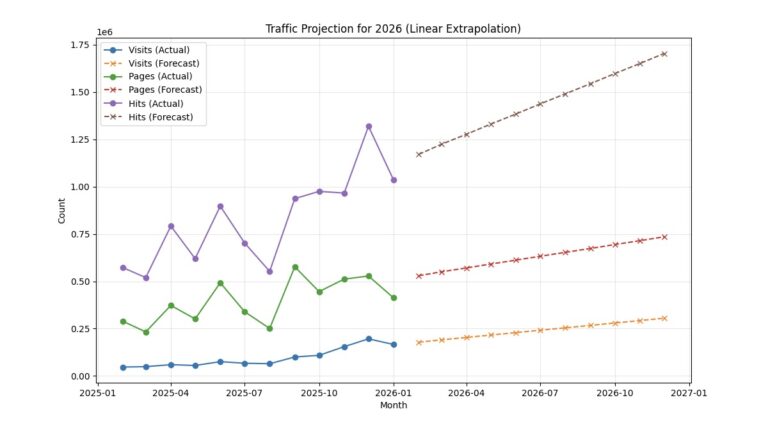

“Their website has a lot of cool information,” Stacey said. “And they’re university researchers. Probably better English than us, honestly. We see lots of traffic on our web site from there too.”

Ben stared at the screen. The pixelated image of the Canadian Shield looked lonely. It always felt lonely out there. The idea that someone else was looking at a similar rock, thinking about similar timescales—thousands of years, radionuclides migrating through groundwater—it made the garage feel a little less isolated.

“They’re doing work on vitrification too,” Stacey added, scrolling again. “Turning the liquid waste into glass. And using materials science to see how barriers hold up to radiation. It’s heavy science. But the film students… maybe they’re trying to explain it. Just like us.”

“AI scriptwriting,” Ben muttered, reading the header on Stacey’s screen over her shoulder. “‘By analyzing existing scripts and audience preferences…’ That sounds a bit soulless, doesn’t it?”

“Maybe,” Stacey shrugged. “Or maybe it’s just a tool. Like that stabilization plugin you love so much. They’re also asking about the ethics of it. ‘How should AI authorship be credited?’ It’s not just tech-bro hype. They’re thinking about it.”

Ben leaned back in his squeaky office chair. The wind rattled the garage door on its tracks. “It’s a long shot, Stacey. They’re a major university in China. We’re… us. Why would they talk to us?”

“Because we’re the only ones crazy enough to be filming rocks in freezing temperatures for an art project?” Jordan offered. “Shared trauma?”

“Because we are the ‘other’ location,” Stacey said seriously. “Beishan and Revell. They are the two models. If they want ‘international context’ for their research, we are literally the only people who can give it to them from a youth perspective. We aren’t the government. We aren’t the nuclear lobby. We’re just… looking at it.”

Ben looked at the unfinished edit on his timeline. The waveform of the wind noise was jagged and red. He looked at the photo of the students in Lanzhou. They looked focused. Serious.

“Okay,” Ben said. He pulled his keyboard closer. “Draft an email. But don’t make it sound too official. If we sound like a corporation, they’ll ignore us. Sound like… us.”

Stacey grinned, opening a new tab. “‘Dear Lanzhou Media Lab, we have a lot of granite and a really buggy VR camera…'”

“Maybe slightly more professional than that,” Ben laughed. “Mention the Revell site first. The geology connection. Then the tech.”

“Right. ‘Subject: Participatory Research and XR Storytelling from the Revell Site, Ontario.'”

“Better,” Jordan noted. “Ask them what microphones they use.”

Ben watched Stacey type. The cursor blinked on the white screen. It felt strange, this sudden pivot. Ten minutes ago, his biggest problem was a loose battery pack and the numbness in his thumb. Now, the scope of the room felt bigger. The walls of the garage seemed to push out a little.

He looked back at his own screen. He opened the colour grading panel. He needed to pull some of the blue out of the shadows, warm up the rock tones just a fraction so it didn’t look quite so bleak. He wondered what the light looked like in Gansu right now. Was it golden hour? Was it harsh noon sun? He imagined the Gobi dust, yellow and fine, settling on a camera lens similar to his.

“What if they use AI to write the reply?” Jordan asked, tossing a chip at Ben.

“Then at least it’ll be grammatically correct,” Ben said. “Hit send, Stacey.”

She hovered over the button. “You think this is weird? Reaching out like this?”

“It’s the internet,” Ben said, looking at the stillness of the rock on his monitor. “Everything is weird. Sending a message to the other side of the planet to talk about rocks that will outlast our civilization? That’s the least weird part of today.”

Stacey clicked. The message swooshed away.

* * *

Later, after Jordan had left and Stacey had gone inside to make tea, Ben sat alone in the garage. The heater clicked off, and the silence rushed back in, heavy and thick.

He picked up the SD card reader, turning the small black square of plastic over in his fingers. It contained gigabytes of data. Light captured, quantized, and stored. In a way, it was its own kind of repository. A memory of a specific afternoon, preserved.

He thought about the students in Lanzhou. He wondered if one of them was sitting in a lab right now, late at night, staring at a monitor, worrying about their future. Worrying about the waste buried beneath their feet, or the algorithms writing their scripts.

He looked out the dirty window of the garage. It was pitch black outside now. The wind had died down, but he could hear the faint hum of the transformer on the pole down the road. Energy. Moving through wires. Leaving waste behind.

He turned back to the screen. He brought up the timeline again. He didn’t play the video. He just looked at the first frame. The grey rock. He imagined a split screen. On the left, Revell. On the right, Beishan. A dialogue of stone.

It felt right. It felt like something that needed to exist.

He rested his hand on the mouse, not moving it, just feeling the cool plastic. For the first time all day, he didn’t feel cold.

THE CLIFFHANGER

“He hit the enter key, sending the message into the dark fiber of the internet, waiting to see if the other side of the world would blink back.”

Unfinished Tales and Short Stories

The Lanzhou Feed is an unfinished fragment from the Unfinished Tales and Short Stories collection, an experimental, creative research project by The Arts Incubator Winnipeg and the Art Borups Corners Storytelling clubs. Each chapter is a unique interdisciplinary arts and narrative storytelling experiment, born from a collaboration between artists and generative AI, designed to explore the boundaries of creative writing, automation, and storytelling. The project was made possible with funding and support from the Ontario Arts Council Multi and Inter-Arts Projects program.

By design, these stories have no beginning and no end. Many stories are fictional, but many others are not. They are snapshots from worlds that never fully exist, inviting you to imagine what comes before and what happens next. We had fun exploring this project, and hope you will too.