Interdisciplinary capacity is the new creative skill—artists learning systems, not just mediums, through hands-on creation.

The System as Curriculum: Rethinking How Northern Ontario Artists Can Learn and Work

Introduction: The Workshop is the Lesson

In every creative generation, there’s a moment when the tools start teaching us. A dancer learns video editing to make her own short films. A musician designs posters because there’s no one else to do it. A writer experiments with sound design and discovers a new rhythm in their prose. The line between disciplines dissolves — not because of theory, but because of necessity, curiosity, and the growing sense that creativity itself has changed.

This is the quiet revolution happening across arts communities in Northern Ontario and beyond: artists learning by making across forms, using technology not as a shortcut, but as a studio. The tool has become the workshop — and the workshop has become the lesson.

The Fall of the Specialist Era

Not long ago, creative work was neatly divided: writers wrote, designers designed, musicians performed. But the realities of working in small communities — where budgets are thin and teams are small — have forced a new kind of adaptability.

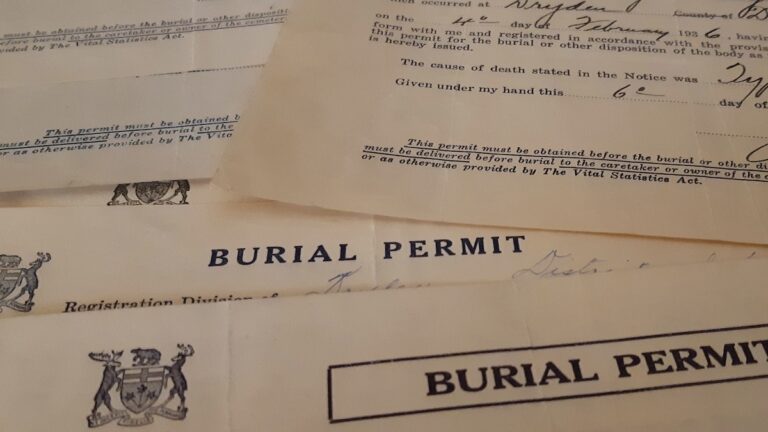

Artists are learning to build their own worlds. A theatre collective might now run its own video archive. A visual artist might publish their own e-book. A musician might produce and distribute their own work, mastering design, metadata, and distribution along the way.

These aren’t “side skills.” They’re survival skills — and, increasingly, creative ones. By necessity, artists in the North are becoming interdisciplinary producers, not through formal training, but through doing. The system they build around their practice — their workflow, their collaborations, their digital tools — becomes its own curriculum.

Learning by Orchestration

This new form of learning doesn’t happen in a classroom. It happens in the act of orchestration — connecting creative, technical, and ethical decisions in real time.

When a visual artist lays out their own exhibition catalogue, they’re learning the logic of design. When a poet formats and distributes their book, they’re gaining procedural literacy — the same kind of systems thinking that software developers rely on.

But this isn’t about becoming a coder or a designer. It’s about learning how systems work — and how to bend them toward creative ends. The creative process becomes a rehearsal for complexity: thinking like a publisher, an archivist, a curator, and a storyteller all at once.

The Atelier Returns

In a way, we’re returning to something ancient. Before the industrial age of specialization, artists learned in ateliers — shared studios where painters, sculptors, and printers worked side by side, trading techniques and materials.

Today’s “digital ateliers” work the same way, except the brushes and chisels are replaced by interfaces and workflows. The principle is unchanged: learning through practice, guided by curiosity and the creative needs of the moment.

What’s emerging isn’t just a new model of art-making — it’s a new form of professional development. Interdisciplinary capacity isn’t something to be taught; it’s something to be lived.

Conclusion: Creativity as a System of Learning

The future of creative capacity building isn’t about mastering every tool or chasing every new medium. It’s about developing the confidence to cross boundaries — to see each new challenge not as a barrier, but as part of the same creative system.

In this sense, the real product of interdisciplinary practice isn’t just the art itself — it’s the artist who emerges more fluent, more connected, and more capable of shaping their own future.

The system is the curriculum. The process is the pedagogy. And the artists of the North are already proving that the best classrooms are the ones we build ourselves.