Where is the art? In this project, the answer is not a single object but a living system. The stories, fragments, analyses, and connective structures form an unseen canvas where meaning emerges through relationship, not completion.

A Few Thoughts for the Unseen Canvas

The question, when it comes, is always delivered with a tilt of the head, a well-meaning furrow of the brow. It’s a question born from centuries of artistic tradition, from a deep and understandable love for the tangible artifact: the painting on the wall, the sculpture in the gallery, the book on the shelf. It’s a question we, as artists working at the intersection of narrative and technology, have come to cherish.

“Where is the art?”

It is the most important question anyone can ask of our work, because its answer does not lie in pointing to a single object. The answer requires a recalibration of seeing. It asks us to look past the finished product and recognize that the gallery itself can be the sculpture; that the rehearsal can be the performance; that the system of creation can be the most profound artwork of all.

In the “Unfinished Tales and Short Stories” project, the art was not just in the random story fragments that appeared on the screen. To find the art, we had to look at the entire ecosystem as a composition. The art is in the architecture of the void.

The Architecture as the Artwork

Imagine a sculptor, but instead of marble or clay, their medium is relationship, context, and potential. This is the foundational artistic practice of our project. The art is in the deliberate, painstaking design of a system that holds and connects our narrative fragments. This was not a technical act of database administration; it was an aesthetic act of world-building.

When we decide that a story fragment must be linked to its genre, its tone, its author, and its thematic keywords, we are making a compositional choice. We are stretching invisible threads of meaning between disparate ideas, creating pathways for discovery that are themselves a form of narrative. The system’s structure is our sculpture. It dictates how one idea flows into another, how a reader can drift from a tale of urban melancholy to one of rural hope, guided not by a linear table of contents but by an emotional or thematic resonance that we, the artists, have woven into the very fabric of the platform.

Each link between a story, its critical analysis, its cinematic treatment, and its final script is a brushstroke. We are not simply storing files in folders; we were learning to map the life-cycle of an idea. We explored making the invisible process of adaptation and interpretation visible, tangible, and navigable. The art is in the revelation that a story is never a single, static thing, but a living entity that breathes, evolves, and transforms across different mediums. The platform itself, in its interconnectedness, became a sprawling, interactive installation about the nature of narrative itself. It argues, through its very design, that the space between different forms of a story is as artistically significant as the forms themselves.

Some say this kind of approach is a new classicism, one where the beauty lies in the elegance of the structure, the harmony of the relationships, and the conceptual integrity of the whole. To ask where the art is, is to stand before a cathedral and ask, “But where is the sculpture?” The art is the cathedral—the buttresses, the arches, the voids, the way the light filters through the stained glass of curated data.

The Process as Performance

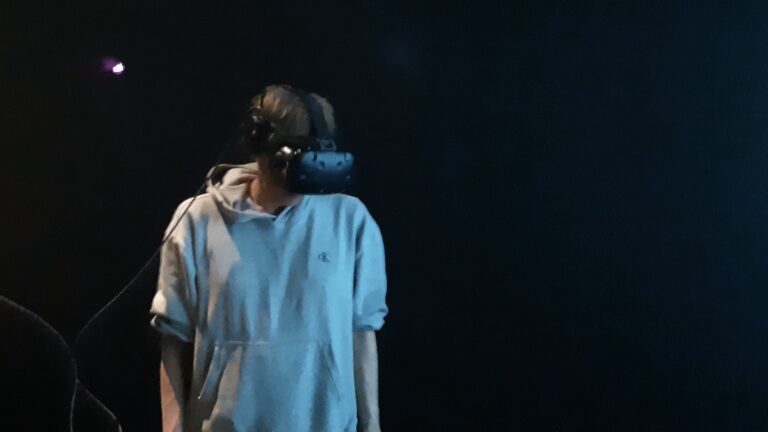

Contemporary art has long recognized that the artistic act can be ephemeral. It can be a performance, a happening, a gesture that exists in time and then vanishes, leaving only its resonance. Our work aimed to explore and embrace this idea completely. The creation of each story fragment is a durational performance, a collaboration between the human artist and a strange, non-human partner: the generative algorithm.

The art is in the dialogue. As an applied artificial intelligence research project, it was in the learning to craft prompts—a process as delicate and intuitive as writing a line of poetry. The prompt is not a command given to a machine; it is an invitation, a provocation, a question posed to a vast, latent space of linguistic possibility. We are not technicians inputting variables; we become choreographers, setting the stage and suggesting the initial movements, then watching, responding, and guiding the dance.

The stream of outputs from generative AI tools is also the raw chaos of the subconscious. Our artistic practice is the act of curating this chaos. We are editors, yes, but we are also alchemists, sifting through mountains of digital lead to find one glint of gold. The art is in the decisions. It is in the moment of recognition when, out of a thousand generated sentences, one rings with the unmistakable clarity of truth, of character, of emotional weight. It is in the rejection of the cliché, the deletion of the facile, the careful selection of the phrase that feels both surprising and inevitable.

This is a performance of judgment, taste, and intuition. It is a slow, meditative practice of listening and responding. It is invisible to the end user, but it was at the very heart of our creative labour. We are shaping the output not by writing every word, but by creating the conditions under which the right words can emerge and then having the wisdom to recognize them when they do. The final texts are merely the artifact of this performance, the libretto of an opera whose true music was the silent, iterative dance between artist and algorithm.

Sometimes good. Sometimes not so good. Sometimes great.

The Fragment as a Complete Poetic Form

There is an implicit critique in the project’s title: “Unfinished Tales and Short Stories.” It suggests a lack, an incompleteness. This is a deliberate misdirection. We assert that the fragment is not an unfinished work; it is a complete and intentional poetic form. Or not.

The art is in the frame. Like a photographer who chooses to frame a single gesture, a sliver of a scene, we choose to frame a single moment in a narrative that has no beginning and no end. We are not failing to write a novel; we are succeeding in capturing an essence. The power of the fragment lies in what it omits. It respects the intelligence and imagination of the reader, inviting them to become a co-creator of the story. The empty space around the text is the most important part of the composition. It is a canvas on which the reader projects their own pasts, their own futures, their own meanings.

Think of a Japanese haiku. Its power is in its brevity, its ability to evoke a world in seventeen syllables. Our fragments operate on the same principle. They are glimpses through a keyhole into a room we can never fully enter. The art is in the crafting of that keyhole—in shaping the scene so perfectly that the reader can sense the entire, unseen world pressing in from all sides. It is an art of implication, of resonance, of restraint.

By presenting these as “unfinished,” we challenge the very notion of artistic completion. Is a story ever truly finished as long as it lives in a reader’s mind? Our work argues that it is not. The story is a catalyst, a seed. The true artistic event happens in the consciousness of the audience, in the quiet, imaginative work they do long after they have navigated away from the page. We are not building a library of endings; we are building a garden of beginnings.

The Project as a Social Sculpture

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the art is in the community that this project incubates and the capacities it builds. The artist Joseph Beuys coined the term “social sculpture” to describe art that takes society itself as its material. Our project is a social sculpture. It is an environment designed to change the way people think about story, technology, and their own creative potential.

When we create a system that is not only a place to read stories but also a place to understand how they are made—complete with analyses, treatments, and methodological essays—we are creating a pedagogical space. We are demystifying the creative process and, in the context of AI, demystifying a technology that is often shrouded in fear and misunderstanding. The art is in the act of empowerment. We are giving artists, writers, and curious minds a new set of tools and, more importantly, a new set of questions.

The project is a studio, a laboratory, and a public square. It is a place for literacy in the 21st century, arguing that understanding how to collaborate with complex systems is a vital creative skill. The art is in the conversations it sparks, the workshops it facilitates, the new ideas it enables in others. It is a living installation that grows and changes not just with the new stories we add, but with every person who engages with it and leaves with a slightly altered perspective on what it means to create.

So, where is the art?

It is a familiar refrain, often delivered with a mixture of genuine curiosity and deep-seated skepticism: “But is it really art?”

For many observers, particularly those from traditional arts councils and funding bodies, the processes and systems at the heart of this project can appear more technical than artistic. The language of “workflows,” “schemas,” and “generative outputs” can feel alienating, seeming to belong more to a software development meeting than an artist’s studio. This skepticism is not born of malice, but of a framework where art is defined by its final, tangible artifact—the singular, finished object that can be hung on a wall, placed on a pedestal, or held in one’s hands.

Our work, by its very nature, resists this definition, and in doing so, it forces an uncomfortable but necessary conversation about what art can be in the 21st century.

The perceived coldness of the “technical” is a misreading of a new kind of artistic craft. The artist’s hand has not vanished; it has simply moved to a different point in the creative process. Where a painter might spend hours mixing pigments to achieve the perfect hue, our artists spend hours crafting prompts to evoke a specific emotional tone. Where a sculptor carves away stone to reveal a form, our curators sift through an abundance of generated text to excavate a single, resonant moment.

The system is not a machine that produces art autonomously; it is an instrument, and like any instrument, it requires immense skill, intuition, and practice to play well. The “architecture” is our composition, the “methodology” is our studio practice. To dismiss this as “not art” is to mistake the loom for the tapestry, the chisel for the sculpture. It is a failure to recognize that the intellectual and aesthetic labor of creation has been relocated to the design of the system itself.

This is not the first time art has been asked to justify its form. Photography was once dismissed as a mere mechanical reproduction, lacking the soul of painting. Conceptual art was derided for prioritizing the idea over the object. Digital art was scorned as something anyone with a computer could do.

In each case, the definition of art had to expand to accommodate a new way of seeing and creating. We are at another such inflection point. By engaging with complex systems and generative tools, we are not abandoning art; we are claiming new territory for it.

We are asking what it means to be an artist in an age of information, where context, relationship, and process are as powerful a medium as oil paint or marble. To turn away from this exploration, to retreat to the comfort of the familiar artifact, is to risk rendering art irrelevant in a world increasingly shaped by the very systems we seek to understand and humanize through our practice.

This project was made possible with funding and support from the Ontario Arts Council Multi and Inter-Arts Projects program and the Government of Ontario. Special thanks to The Arts Incubator Winnipeg, Art Borups Corners; Melgund Recreation, Arts and Culture and the Minneapolis College of Art and Design Creative Entrepreneurship program.