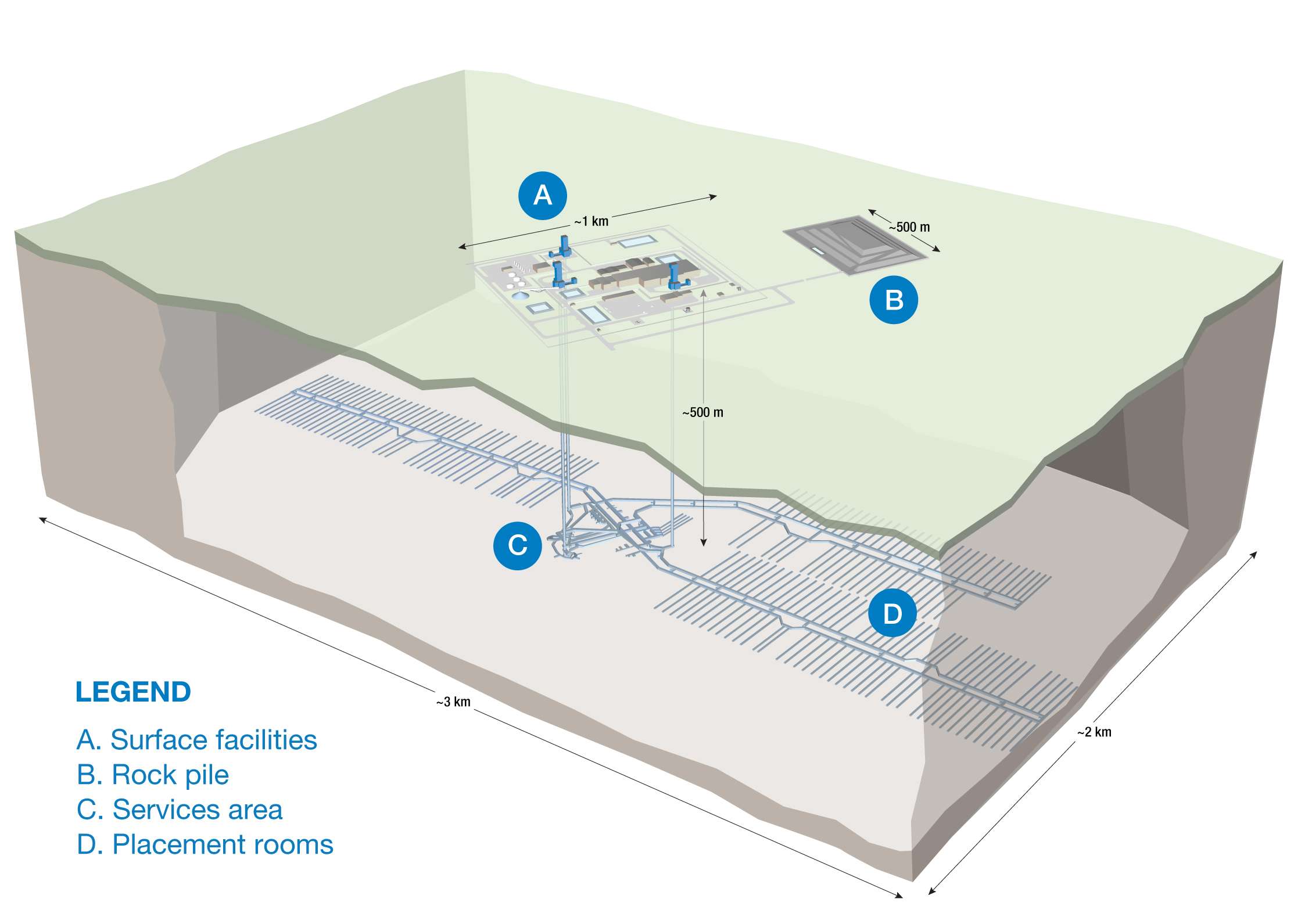

This photo is a rendering of the proposed Deep Geological Repository (DGR) at the Revell Site, designed to safely store nuclear waste deep underground for long-term environmental protection.

What are people saying?

Today’s report presents a comprehensive meta-analysis of public comments submitted to the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada (IAAC) regarding the Initial Project Description for the proposed Revell Site Deep Geological Repository (DGR). The scope of this analysis encompasses 61 distinct assessments of submissions from individuals, municipalities, Indigenous groups, and non-governmental organizations. The objective is to synthesize the diverse perspectives regarding the plan to store high-level nuclear waste in Northwestern Ontario.

Click here to read the public comments.

The analysis reveals a stark division in public sentiment, with the overwhelming majority of submissions expressing deep concern or rejection of the project. A quantitative breakdown of the reviewed assessments indicates that approximately 85.2% of commenters are Opposed to the project, 9.8% are in Support, and 4.9% remain Neutral or focused solely on procedural inquiries. This report categorizes the specific arguments raised by these stakeholders to provide a clear understanding of the public discourse.

Consolidated Overview

The consolidated feedback indicates a prevailing sentiment of distrust, anxiety, and skepticism regarding the Nuclear Waste Management Organization’s (NWMO) proposal. While a small minority of submissions—primarily technical rebuttals—support the project based on scientific data regarding radiation decay and cask safety, the dominant narrative is one of resistance. Opponents characterize the project not as a solution, but as an “irreversible experiment” that threatens the environmental integrity of the Canadian Shield. There is a strong consensus among critics that the project is being rushed through a regulatory framework that fails to account for the full scope of risks, particularly regarding transportation and long-term containment.

Qualitatively, the opposition is rooted in both technical fears and ethical objections. Commenters frequently cite the “unproven” nature of deep geological storage and the impossibility of guaranteeing safety over a timeframe of one million years. Conversely, the supporting comments frame the opposition as being driven by “misinformation” and argue that the DGR is a federal mandate necessary for responsible waste stewardship. Despite these supporting arguments, the sheer volume of opposition suggests a significant lack of social license for the project, particularly among Indigenous communities and municipalities located along the proposed transportation corridors.

Key Issues Analysis

Environment

The most frequently cited environmental concern is the potential for catastrophic water contamination. Commenters repeatedly highlighted the location of the Revell site at the headwaters of the Wabigoon and Turtle-Rainy River watersheds, which flow into Lake Winnipeg and eventually Hudson Bay. There is a profound fear that any failure in the repository’s containment—whether through corrosion, rock fracturing, or human error—would irreversibly poison the water supply for downstream communities and ecosystems. Critics argue that the porous nature of limestone and the unpredictability of geological shifts over millennia make the site unsuitable for storing toxic materials that remain hazardous for hundreds of thousands of years.

Beyond immediate water risks, submissions raised significant doubts regarding the geological stability of the Canadian Shield. While proponents argue the rock formation is stable, opponents suggest that boring into the bedrock could destabilize the segment, citing risks of seismic activity or even volcanic formation over geological timescales. The concept of “retrievability” was also a major point of contention; many commenters argued that burying the waste renders it irretrievable in the event of a leak, turning a management problem into a permanent environmental disaster. This is contrasted by supporting views that emphasize the technical validity of the multi-barrier system and the eventual decay of radioactivity to levels comparable to natural uranium ore.

The environmental discourse also encompasses the broader climate crisis. Opponents vehemently reject the framing of nuclear energy as a “clean” solution, describing the DGR as an enabler for a “dirty” industry that produces toxic waste with no safe disposal method. They argue that the resources allocated to the DGR would be better spent on renewable technologies like wind and solar. Conversely, supporters argue that the DGR is essential for Canada’s net-zero goals, asserting that nuclear power provides baseload reliability that renewables cannot match, and that a closed-loop fuel cycle could eventually allow for the recycling of waste into new energy resources.

Transportation

A critical procedural and safety red flag identified in the assessments is the exclusion of transportation logistics from the Initial Project Description. Numerous commenters, including the Town of Latchford, argued that the transport of waste is an integral component of the project and its exclusion renders the impact assessment “legally and procedurally flawed.” Residents along the Trans-Canada Highway (Highways 11 and 17) expressed outrage that they are expected to bear the risks of a “mobile Chernobyl”—thousands of shipments of high-level radioactive waste over decades—without being formally included in the decision-making process or the project’s scope.

The physical dangers of the proposed transport routes were detailed extensively. Commenters described the highways in Northern Ontario as hazardous, citing frequent accidents, “terrible weather conditions,” and limited infrastructure. The prospect of 2 to 3 trucks per day carrying radioactive payloads on two-lane, icy roads was characterized as a statistical inevitability for disaster. Concerns were raised regarding the durability of transport casks under high-impact scenarios, such as collisions or fires, and the potential for “fuel bundle damage” due to vibration during long-haul transit, which could complicate handling at the repository site.

Emergency response capabilities emerged as a tertiary concern within this category. Rural and Indigenous communities along the route emphasized that they lack the training, equipment, and funding to manage a radioactive spill or fire. They fear that a transportation accident would not only cause immediate health risks but would also sever vital supply lines, isolating communities that rely on a single highway for food and medical services. Supporters attempted to counter these fears by citing the 2024 Emergency Response Guidebook and international safety records, arguing that nuclear transport is safer than moving common industrial chemicals like ammonia or propane.

Governance

The assessments reveal a profound crisis of confidence in the regulatory bodies and the NWMO. Many commenters view the NWMO not as a neutral arbiter, but as an industry-led organization engaged in “regulatory capture.” Critics argue that the organization is prioritizing the nuclear industry’s need to dispose of waste over public safety. This distrust is exacerbated by what is perceived as a “rushed” consultation process; multiple submissions criticized the inadequacy of a 30-day window to review thousands of pages of technical documentation, labeling it “patently unfair” and undemocratic.

A significant governance issue involves the definition and acquisition of consent. Commenters raised red flags regarding “consent manufacturing” and “consent buying,” pointing to the financial incentives offered to potential host communities like Ignace. Critics argue that these payments distort the democratic process, effectively bribing small, economically struggling townships to accept risks that affect a much broader region. There is a strong demand for a wider definition of “host community” that includes those downstream and along transport corridors, rather than limiting decision-making power to the immediate municipality surrounding the dig site.

Furthermore, the lack of transparency and the perceived suppression of dissenting voices were recurring themes. Submissions noted that the current process allows the NWMO to bypass the concerns of “corridor communities” and Indigenous groups who have not signed agreements. The call for a province-wide referendum or a more inclusive federal assessment reflects a belief that the current governance structure is designed to secure approval rather than to genuinely assess feasibility and social acceptability. The exclusion of transportation from the formal scope is viewed as a tactical maneuver to avoid scrutiny from the thousands of citizens living along the route.

Ethics

The central ethical argument against the DGR is the violation of intergenerational equity. Commenters frequently invoked the “Seven Generations” principle, arguing that it is morally wrong to bury toxic waste that will remain hazardous for a million years, effectively “shoveling” the problem onto future descendants who will have no say in the matter. This act is described as “inherent short-sightedness” and a failure of stewardship. Opponents contend that the current generation, having benefited from the energy, has no right to impose a lethal legacy on a future that may lack the institutional capacity to manage it.

A second ethical dimension involves environmental justice and the distribution of risk. Commenters highlighted the inequity of transporting waste from Southern Ontario, where the energy was consumed and the economic benefits realized, to Northern Ontario. This is framed as a form of “colonialism” or regional exploitation, where the North is treated as a dumping ground for the South’s hazardous byproducts. The submissions argue that the waste should remain near the point of generation, forcing the beneficiaries of the nuclear industry to live with the consequences of their energy choices.

Finally, the connection between nuclear energy and global security was raised as a serious ethical concern. Several assessments linked the nuclear fuel cycle to the proliferation of nuclear weapons, describing the industry as a “madness” that threatens human survival. The ethical stance here is one of total rejection; commenters argue that if a safe disposal method does not exist—and they believe the DGR is not safe—then the ethical imperative is to cease the production of nuclear waste entirely, rather than justifying its continued generation through “utopian” disposal schemes.

Indigenous Rights

The violation of Indigenous rights and the failure to adhere to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) are central themes in the opposition. Submissions from groups such as the Eagle Lake First Nation and Grassy Narrows First Nation assert that the project is proceeding without their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC). The Eagle Lake First Nation specifically noted a territorial dispute, arguing they have been improperly denied recognition as a host community despite the project impacting their traditional lands.

The legacy of “environmental racism” is a palpable undercurrent, particularly in submissions referencing Grassy Narrows, a community already devastated by mercury poisoning. Commenters argue that placing a nuclear repository in proximity to these communities compounds historical traumas and represents a continued disregard for Indigenous lives and health. The opposition is not merely political but spiritual; the extraction of rock and the burial of waste are viewed as violations of the sacred relationship between the people and the Land (Mother Earth).

Furthermore, the assessments highlight a divide between band councils that may have signed agreements and the broader community members who oppose the project. The submission from “We the Nuclear Free North” indicates that despite some official agreements, there is widespread grassroots opposition within Treaty #3 territory. Critics argue that the NWMO’s engagement strategies have been divisive, pitting communities against one another and failing to respect the collective decision-making processes mandated by Indigenous Law and sovereignty.

Socio-Economic

Economic concerns are framed largely around the cost-benefit disparity of nuclear energy versus renewables. Opponents argue that nuclear power is the “most expensive” form of energy and that the DGR is a massive financial liability that will ultimately be borne by taxpayers. They contend that the billions of dollars required for the repository could be better invested in sustainable infrastructure, healthcare, or education. There is also skepticism regarding the NWMO’s budget transparency, with demands for a full financial breakdown of the project.

At the local level, fears regarding the “stigma” of becoming a nuclear waste dump were prominent. Residents and business owners in Northwestern Ontario worry that the presence of the DGR will destroy the region’s reputation as a pristine wilderness destination, thereby collapsing the tourism and outdoor recreation industries. The potential loss of property values and the degradation of the “brand” of the North are seen as long-term economic threats that outweigh any temporary jobs created during the construction phase.

Conversely, the minority of supporting comments present a different socio-economic perspective, viewing the waste as a potential “multi-trillion-dollar resource.” These submissions advocate for recycling spent fuel in advanced reactors, arguing that burying the waste is an economic waste of valuable energy potential. However, the dominant socio-economic narrative remains one of risk, with communities fearing that a single accident—whether on the road or at the site—would lead to economic ruin through the contamination of the land and water upon which their livelihoods depend.

Community Suggestions

The public comments offer several constructive alternatives and demands regarding the management of nuclear waste:

- Rolling Stewardship / On-Site Storage: The most common suggestion is to abandon the DGR concept in favor of “hardened” on-site storage at the nuclear reactor sites. This approach keeps the waste accessible, monitorable, and retrievable, avoiding the risks of transportation and allowing future generations to apply new technologies.

- Full Federal Impact Assessment: There is a near-universal demand among opponents for a comprehensive Impact Assessment that explicitly includes transportation within its scope. This would necessitate the evaluation of risks to all corridor communities and watersheds, not just the immediate repository site.

- Referendum: Several commenters called for a province-wide referendum to ensure that all Ontarians, particularly those along transport routes, have a democratic say in the project.

- Recycling and Reprocessing: A minority of commenters suggested investing in technology to recycle spent nuclear fuel (breeder reactors) to reduce the volume of waste and utilize the remaining energy content, rather than permanent burial.

- Policy Shift to Renewables: A broad strategic suggestion is the immediate cessation of nuclear energy production (“No more nukes”) in favor of wind, solar, and geothermal energy to stop adding to the waste inventory.

Want to learn more? Visit our project page at: https://melgundrecreation.ca/nuclear