A photo essay from the heart of Tornado Alley

by Ethan Caners

April 30th to May 14th, 2023

After taking part in the Our People Our Climate workshop held this February, I was able to travel to the United States in Texas and Kansas and put my photography and photo storytelling skills to the test. Here are some of my favourite photos.

As the global average temperature increases, these storms will be fed warmer air to convect from, causing severe storms unlike anything we have seen so far. Sadly at this time, there’s near nothing we can do except be prepared.

If you would like to watch the workshop, which was organized by the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, youth from Columbia and the United Nations Environment Program, click here.

A majestic corkscrew supercell (low precipitate rear flank mesocyclone) explodes in strength East Southeast of Moore, Oklahoma. These specific supercells are formed when a rotating updraft collides wind shear from the Jetstream.

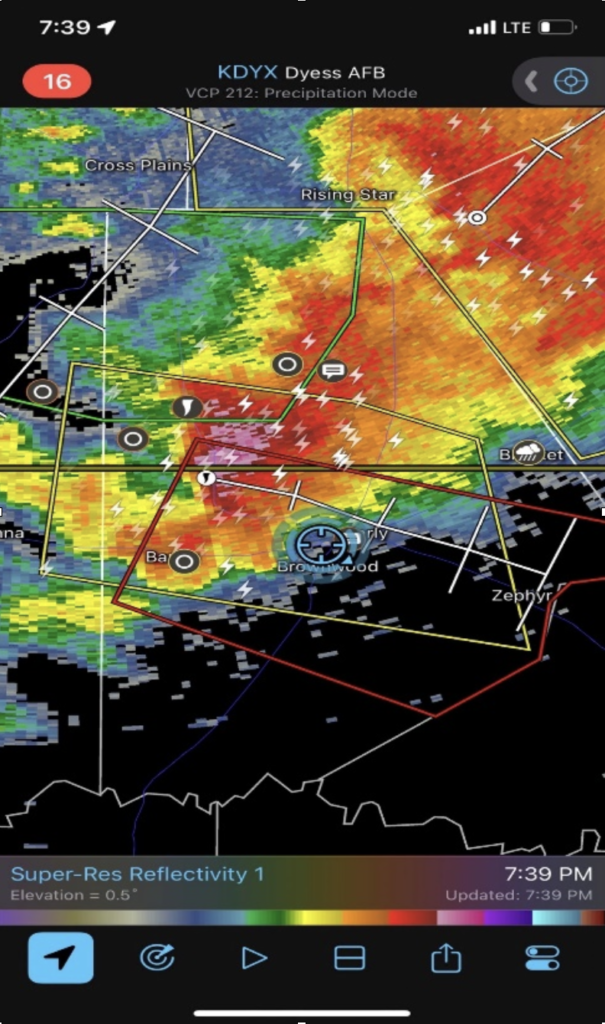

Stationed in Brownwood, Texas on May the sixth, this erratic cell showed signs of tornadogenesis, the process of how tornados form. As we all watched in amazement, the NWS (National Weather Services) issued a tornado warning for the town’s county, accompanied by the blaring sirens that echoed through the empty streets. Luckily, the rotation never reached the surface, sparing the town of nearly 20,000 people.

An RFD (rear flank downdraft) behind a rotating wall cloud as a base slowly begins to form in this system northeast of Amarillo, Texas

The radar image above shows the high-resolution reflectivity of this tornado warned system as it approaches our position. The blue circle is where the image to the left was shot from, looking into the small low precipitate notch to our Northwest.

In this eery shot, a LRWC (lowered rotating wall cloud) produced intense downburst winds 5 miles east of Larned, Kansas. As this system moved into warmer air, it produced multiple funnels and intense dust vortices.

With a looming tornado watch over half the state of Kansas, this photogenic mothership style supercell travelled from Kinsley to the west northwest of Great Bend, Kansas. This storm was part of a QLCS lines (quasilinear convection system, also known as squall lines) southwest portion, where most QLCS tornadoes will emerge from.

With the LLJ (low level jets) kicking in at 6pm in central Kansas, this incredible scud clouds warping around this lowered wall cloud, and as the updrafts intensifies, the pancake effect you see above the wall cloud also increased in layers.

The duality of a storm can often be fascinating. During a late-night thunderstorm shoot, we took two long exposure pictures. The ominous scene to the left is the south facing shot, whereas a single 180-degree turn shows the constellations of the universe.

Same spot, different angle.

As the storm wither away with the cold front, the mammatus clouds take shape on the edge of the anvil, (left) but after the storms dissipate, the other side of storm chasing begins. When damage to a populated residence is observed, you become the first responder.

The golden rules of tracking these dangerous storms goes as follows. “When you see damage, your chase is over. Even if the tornado is on the ground but you’re in a safe area, search and rescue begins.” This saying was taught to me by my chasing partner Jordan Carruthers, who then applied the saying after the EF2 Hooper to Oakland Nebraska tornado. The shot above shows Jordan Carruthers and myself rushing to assist in the potential rescue of the homeowners, which luckily were not in the house at the time. (Photo credit to Shannon Bileski).